Kapeina

| |

| |

| Datos Klinikal | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | monograph |

| Kategorya sa pagdadalangtao |

|

| Dependence liability | Physical: low–moderate[1][2][3] Psychological: low[4] |

| Pananagutang adiksyon | None[1][2]–low[3] |

| Mga ruta ng administrasyon | By mouth, insufflation, enema, rectal, intravenous |

| Klase ng Droga | Stimulant Adenosinergic Eugeroic Parasympathomimetic Cholinesterase inhibitor Phosphodiesterase inhibitor Diuretic |

| Kodigong ATC | |

| Estadong Legal | |

| Estadong legal |

|

| Datos Parmakokinetiko | |

| Bioavailability | 99%[5] |

| Pagbuklod ng protina | 25–36%[6] |

| Metabolismo | Primary: CYP1A2[6] Minor: CYP2E1,[6] CYP3A4,[6] CYP2C8,[6] CYP2C9[6] |

| Mga Metabolite | Paraxanthine (84%) Theobromine (12%) Theophylline (4%) |

| Bugso ng aksyon | 45 minutes–1 hour[5][7] |

| Biyolohikal na hating-buhay | Adults: 3–7 hours[6] Infants (full term): 8 hours[6] Infants (premature): 100 hours[6] |

| Tagal ng aksyon | 3–4 hours[5] |

| Ekskresyon | Urine (100%) |

| Mga pangkilala | |

| |

| Singkahulugan | Guaranine Methyltheobromine 1,3,7-Trimethylxanthine 7-methyltheophylline[8] Theine |

| Bilang ng CAS | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.329 |

| Datos Kemikal at Pisikal | |

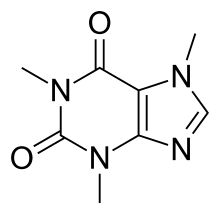

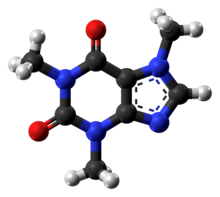

| Pormula | C8H10N4O2 |

| Bigat Molar | 194.19 g·mol−1 |

| Modelong 3D (Jmol) | |

| Densidad | 1.23 g/cm3 |

| Punto ng pagkatunaw | 235 hanggang 238 °C (455 hanggang 460 °F) (anhydrous)[9][10] |

| |

| |

Ang kapeina ay isang Gitnang sistemang nerbyos (CNS) stimulant ng isang klase ng methylxanthine.[11] Ito ay ginagamit bilang cognitive enhancer, pagpapataas ng positibo at tungkulin ng pagpasigla.[12][13] Ang kapeina ay kumikilos sa pamamagitan ng pagharang sa pagbubuklod ng adenosine sa adenosine A 1 receptor, na naipapahusay sa pagpapalabas ng neurotransmitter na asetilkolina .[14] Pinapataas din ng kapeina ang mga antas ng cyclic AMP sa pamamagitan ng nonselective inhibition ng phosphodiesterase.[15]

Ang kapeina ay isang mapait, maputi mala-kristal na purine, isang methylxanthine alkaloid, at may kemikal na kaugnayan sa adenine at guanine base ng deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) at ribonucleic acid (RNA). Ito ay matatagpuan sa mga buto, prutas, mani, o dahon ng ilang halaman na katutubo sa Afrika, Silangang Asya at Timog Amerika, at tumutulong upang maprotektahan ang mga ito laban sa mga herbivore at mula sa kompetisyon sa pamamagitan ng pagpigil sa pagtubo ng mga kalapit na buto, pati na rin ang paghikayat sa pagkonsumo ng mga piling hayop tulad ng Pukyutan.[16] Ang mas popular na pinagmulan na panghinakas na sangkap ng kapeina ay ang butil ng kape, ang buto ng halaman ng Coffea . Ang mga tao ay maaaring uminom ng mga inuming naglalaman ng kapeina upang mapawi o maiwasan ang pangaantok at upang mapabuti ang pagganap ng pag-iisip. Upang gawin ang mga inuming ito, ang kapeina ay kinukuha sa pamamagitan ng pagtarik ng mga produkto ng halaman sa tubig, isang prosesong tinatawag na inpusyon . Ang mga inuming ma merong kapeina, tulad ng kape, tsaa, at cola, ay maraming konsyumo nito sa buong mundo at mataas ng - kailangang mg paggamit nito sa lipunan. Noong 2020, halos 10 milyong tonelada ng butilng kape ang nakonsumo sa buong mundo.[17] Ang kapeina ay ang pinakalawak na ginagamit na psychoactive na gamot sa mundo.[18][19] Hindi tulad ng karamihan sa iba pang mga psychoactive substance, ang kapeina ay nananatiling hindi kinokontrol at legal sa halos lahat ng bahagi ng mundo. Ang kapeina ay isa ring panlabas na linya dahil ang paggamit nito ay nakikita bilang katanggap-tanggap sa lipunan sa karamihan ng mga kultura at kahit na hinihikayat sa iba, lalo na sa Kultura ng lipunang Kanluran.

Ang kapeina ay maaaring magkaroon ng parehong positibo at negatibong epekto sa kalusugan. Nagagamot at napipigilan nito ang napaaga na mga karamdaman sa paghinga ng sanggol na bronchopulmonary dysplasia ng pagbata at apnea ng prematurity. Ang kapeina citrate ay nasa Listahan ng WHO Model List of Essential Medicines . Maaari itong magbigay ng katamtamang proteksiyon na epekto laban sa ilang sakit,[20] kabilang ang Karamdamang Parkinson.[21] Ang ilang mga tao ay nakakaranas ng pagkagambala sa pagtulog o pagkabalisa kung kumakain sila ng kapeina,[22] ngunit ang iba ay nagpapakita ng kaunting simptomas. Ang katibayan nito ng isang panganib sa pagsasanggol ay hindi maliwanag; inirerekomenda rin ng ilang awtoridad na limitahan ng mga buntis na kababaihan ang kapeina sa katumbas ng dalawang tasa ng kape bawat araw o mas kaunti.[23][24] Ang kapeina ay maaaring makagawa ng banayad na anyo ng pag-asa sa droga – nauugnay sa mga sintomas ng paghulog tulad ng pagkaantok, sakit ng ulo, at pagkamayamutin – kapag ang isang indibidwal ay huminto sa paggamit ng kapeina pagkatapos ng paulit-ulit na pang-araw-araw na paggamit.[4] Áng pagparaya sa mga awtonomic na epekto ng tumaas na presyon ng dugo at tibok ng puso, at pagtaas ng paglabas ng ihi, ay nabubuo sa talamak na paggamit (ibig sabihin, ang mga sintomas na ito ay hindi gaanong binibigkas o hindi nangyayari pagkatapos ng pare-parehong paggamit).[25]

Ang kapeina ay sinuri ng US Food and Drug Administration bilang pangkalahatang kinikilala bilang ligtas na gamitin na gamot. Iniulat ng European Food Safety Authority na hanggang 400 mg ng kapeina bawat araw (sa paligid ng 5.7 mg/kg ng body mass bawat araw) ay hindi nagpapataas ng mga nagaalala para sakaligtasan at sa mga hindi buntis na nasa hustong gulang, habang umiinom ng hanggang 200 Ang mg bawat araw para sa mga buntis at nagpapasusong kababaihan ay hindi naglalabas ng mga alalahanin sa kaligtasan para sa fetus o mga sanggol na pinapasuso.[26] Ang isang tasa ng kape ay naglalaman ng 80–175 mg ng kapeina, depende sa kung anong "butil" (binhi) ang ginagamit, kung paano ito iniihaw (mas kaunting kapeina ang mga dark roast), at kung paano ito inihahanda (hal., drip, percolation, o espresso ). Kaya nangangailangan ito ng humigit-kumulang 50–100 ordinaryong tasa ng kape upang maabot ang nakakalason na dosis. Gayunpaman, ang purong powdered kapeina, na available bilang dietary supplement, ay maaaring nakamamatay sa laki ng kutsara.

Mga sanggunian

[baguhin | baguhin ang wikitext]- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". Sa Sydor A, Brown RY (mga pat.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (ika-2nd (na) edisyon). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 375. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

Long-term caffeine use can lead to mild physical dependence. A withdrawal syndrome characterized by drowsiness, irritability, and headache typically lasts no longer than a day. True compulsive use of caffeine has not been documented.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link) - ↑ 2.0 2.1 American Psychiatric Association (2013). "Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders" (PDF). American Psychiatric Publishing. pp. 1–2. Inarkibo mula sa orihinal (PDF) noong 15 Agosto 2015. Nakuha noong 10 Hulyo 2015.

Substance use disorder in DSM-5 combines the DSM-IV categories of substance abuse and substance dependence into a single disorder measured on a continuum from mild to severe. ... Additionally, the diagnosis of dependence caused much confusion. Most people link dependence with "addiction" when in fact dependence can be a normal body response to a substance. ... DSM-5 will not include caffeine use disorder, although research shows that as little as two to three cups of coffee can trigger a withdrawal effect marked by tiredness or sleepiness. There is sufficient evidence to support this as a condition, however it is not yet clear to what extent it is a clinically significant disorder.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link) - ↑ 3.0 3.1 Introduction to Pharmacology (ika-third (na) edisyon). Abingdon: CRC Press. 2007. pp. 222–223. ISBN 978-1-4200-4742-4. Inarkibo mula sa orihinal noong 14 Enero 2023. Nakuha noong 25 Agosto 2017.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link) - ↑ 4.0 4.1 Juliano LM, Griffiths RR (Oktubre 2004). "A critical review of caffeine withdrawal: empirical validation of symptoms and signs, incidence, severity, and associated features". Psychopharmacology. 176 (1): 1–29. doi:10.1007/s00213-004-2000-x. PMID 15448977.

Results: Of 49 symptom categories identified, the following 10 fulfilled validity criteria: headache, fatigue, decreased energy/ activeness, decreased alertness, drowsiness, decreased contentedness, depressed mood, difficulty concentrating, irritability, and foggy/not clearheaded. In addition, flu-like symptoms, nausea/vomiting, and muscle pain/stiffness were judged likely to represent valid symptom categories. In experimental studies, the incidence of headache was 50% and the incidence of clinically significant distress or functional impairment was 13%. Typically, onset of symptoms occurred 12–24 h after abstinence, with peak intensity at 20–51 h, and for a duration of 2–9 days.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link) - ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Poleszak E, Szopa A, Wyska E, Kukuła-Koch W, Serefko A, Wośko S, Bogatko K, Wróbel A, Wlaź P (Pebrero 2016). "Caffeine augments the antidepressant-like activity of mianserin and agomelatine in forced swim and tail suspension tests in mice". Pharmacological Reports. 68 (1): 56–61. doi:10.1016/j.pharep.2015.06.138. PMID 26721352. S2CID 19471083.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link) - ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 "Caffeine". DrugBank. University of Alberta. 16 Setyembre 2013. Inarkibo mula sa orihinal noong 4 Mayo 2015. Nakuha noong 8 Agosto 2014.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch (tulong)CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link) - ↑ Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Military Nutrition Research (2001). "2, Pharmacology of Caffeine". Pharmacology of Caffeine (sa wikang Ingles). National Academies Press (US). Inarkibo mula sa orihinal noong 28 Setyembre 2021. Nakuha noong 15 Disyembre 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link) - ↑ "Caffeine". ChemSpider. Inarkibo mula sa orihinal noong 14 Mayo 2019. Nakuha noong 16 Nobyembre 2021.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch (tulong)CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link) - ↑ "Caffeine". Pubchem Compound. NCBI. Nakuha noong 16 Oktubre 2014.

Boiling Point

178 °C (sublimes)

Melting Point

238 DEG C (ANHYD){{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link) - ↑ "Caffeine". ChemSpider. Royal Society of Chemistry. Inarkibo mula sa orihinal noong 14 Mayo 2019. Nakuha noong 16 Oktubre 2014.

Experimental Melting Point:

234–236 °C Alfa Aesar

237 °C Oxford University Chemical Safety Data

238 °C LKT Labs [C0221]

237 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 14937

238 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 17008, 17229, 22105, 27892, 27893, 27894, 27895

235.25 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 27892, 27893, 27894, 27895

236 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 27892, 27893, 27894, 27895

235 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 6603

234–236 °C Alfa Aesar A10431, 39214

Experimental Boiling Point:

178 °C (Sublimes) Alfa Aesar

178 °C (Sublimes) Alfa Aesar 39214{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch (tulong)CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link) - ↑ Nehlig A, Daval JL, Debry G (1992). "Caffeine and the central nervous system: mechanisms of action, biochemical, metabolic and psychostimulant effects". Brain Research. Brain Research Reviews. 17 (2): 139–170. doi:10.1016/0165-0173(92)90012-B. PMID 1356551.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link) - ↑ Camfield DA, Stough C, Farrimond J, Scholey AB (Agosto 2014). "Acute effects of tea constituents L-theanine, caffeine, and epigallocatechin gallate on cognitive function and mood: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Nutrition Reviews. 72 (8): 507–522. doi:10.1111/nure.12120. PMID 24946991.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link) - ↑ Wood S, Sage JR, Shuman T, Anagnostaras SG (Enero 2014). "Psychostimulants and cognition: a continuum of behavioral and cognitive activation". Pharmacological Reviews. 66 (1): 193–221. doi:10.1124/pr.112.007054. PMC 3880463. PMID 24344115.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link) - ↑ Carter AJ, O'Connor WT, Carter MJ, Ungerstedt U (Mayo 1995). "Caffeine enhances acetylcholine release in the hippocampus in vivo by a selective interaction with adenosine A1 receptors". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 273 (2): 637–642. PMID 7752065.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link) - ↑ Faudone G, Arifi S, Merk D (Hunyo 2021). "The Medicinal Chemistry of Caffeine". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 64 (11): 7156–7178. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00261. PMID 34019396.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link) - ↑ Wright GA, Baker DD, Palmer MJ, Stabler D, Mustard JA, Power EF, Borland AM, Stevenson PC (Marso 2013). "Caffeine in floral nectar enhances a pollinator's memory of reward". Science. 339 (6124): 1202–4. Bibcode:2013Sci...339.1202W. doi:10.1126/science.1228806. PMC 4521368. PMID 23471406.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link) - ↑ "Global coffee consumption, 2020/21". Statista.

- ↑ "What's your poison: caffeine". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 1997. Inarkibo mula sa orihinal noong 26 Hulyo 2009. Nakuha noong 15 Enero 2014.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link)Burchfield G (1997). Meredith H (ed.). . Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 26 July 2009. Retrieved 15 January 2014. - ↑ Jamieson, Ross W. (2001). "The Essence of Commodification: Caffeine Dependencies in the Early Modern World". Journal of Social History. 35 (2): 269–294. ISSN 0022-4529.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link)Jamieson, Ross W. (2001). "The Essence of Commodification: Caffeine Dependencies in the Early Modern World". Journal of Social History. 35 (2): 269–294. ISSN 0022-4529. - ↑ Cano-Marquina A, Tarín JJ, Cano A (Mayo 2013). "The impact of coffee on health". Maturitas. 75 (1): 7–21. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.02.002. PMID 23465359.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link)Cano-Marquina A, Tarín JJ, Cano A (May 2013). "The impact of coffee on health". Maturitas. 75 (1): 7–21. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.02.002. PMID 23465359. - ↑ Qi H, Li S (Abril 2014). "Dose-response meta-analysis on coffee, tea and caffeine consumption with risk of Parkinson's disease". Geriatrics & Gerontology International. 14 (2): 430–9. doi:10.1111/ggi.12123. PMID 23879665.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link)Qi H, Li S (April 2014). "Dose-response meta-analysis on coffee, tea and caffeine consumption with risk of Parkinson's disease". Geriatrics & Gerontology International. 14 (2): 430–9. doi:10.1111/ggi.12123. PMID 23879665. S2CID 42527557. - ↑ O'Callaghan F, Muurlink O, Reid N (7 Disyembre 2018). "Effects of caffeine on sleep quality and daytime functioning". Risk Management and Healthcare Policy. 11: 263–271. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S156404. PMC 6292246. PMID 30573997.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link) - ↑ Jahanfar S, Jaafar SH (Hunyo 2015). "Effects of restricted caffeine intake by mother on fetal, neonatal and pregnancy outcomes". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD006965. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006965.pub4. PMID 26058966.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link) - ↑ American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (Agosto 2010). "ACOG CommitteeOpinion No. 462: Moderate caffeine consumption during pregnancy". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 116 (2 Pt 1): 467–8. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181eeb2a1. PMID 20664420.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link) - ↑ Robertson D, Wade D, Workman R, Woosley RL, Oates JA (Abril 1981). "Tolerance to the humoral and hemodynamic effects of caffeine in man". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 67 (4): 1111–7. doi:10.1172/JCI110124. PMC 370671. PMID 7009653.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link) - ↑ "Scientific Opinion on the safety of caffeine". EFSA Journal (sa wikang Ingles). 13 (5): 4102. 2015. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2015.4102. ISSN 1831-4732. Inarkibo mula sa orihinal noong 15 Hulyo 2021. Nakuha noong 15 Hulyo 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link)