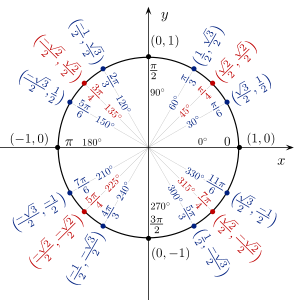

Ang mga cosine at sine sa loob ng isang bilog na unit Ang trigonometriya o trigonometrya (Bagong Latin : trigōnometria , mula sa Sinaunang Griyego : trígōnon -metron [ 1] tatsihaan [ 2] matematika na isang pag-aaral ng mga tatsulok , partikular iyong mga tatsulok na plano (plane ) na may sulok na 90 digri (right triangle o tamang tasulok) at ang mga kaugnayan sa pagitan ng mga gilid at ang ang mga anggulo ng mga gilid na ito. Ang trigonometriya ay naglalarawan din ng mga punsiyon na trigonometriko na ginagamit sa pagmomodelo o pag-unawa ng mga siklikal (paulit ulit) na mga penomena sa kalikasan gaya ng mga alon (waves). Ang trigonometriya ay nabuo noong ikatlong siglo BCE bilang sangay ng heometriya at ito'y malawakang ginamit sa pag-aaral ng astronomiya . Ito rin ang pundasyon ng pagsusukat (surveying). Ang trigonometriya ay karaniwang itinuturo sa mga estudyante ng hayskul.

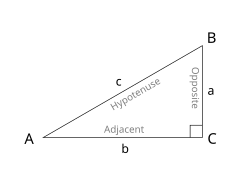

Sa tamang tatsulok (right triangle): sin A = a /c ; cos A = b /c ; tan A = a /b . Sa heometriya , ang isang anggulo ay isang pigura na nabubuo ng dalawang sinag (ray) ng pinagsasamang dulo ng tuldok (endpoint), na tinatawag na berteks (vertex) ng anggulo. Kung ang isa sa anggulo ng isang tatsulok ay may 90 na digri at ang isa pang anggulo ay alam, ang ikatlo ay matutukoy din, dahil ang tatlong mga anggulo ng anumang tatsulok ay binubuo ng 180 digri. Ang pinagsamang dalawang akyut na mga anggulo ay may sukat na 90 digri: ang tawag dito ay mga "komplementaryong mga anggulo". Ang hugis ng isang tatsulok ay ganap na matutukoy maliban sa pagkakapareho ng mga anggulo. Kapag alam ang mga anggulo, ang mga rasyo (ratio) ng mga gilid ay matutukoy kahit ano pa ang kabuuang sukat ng tatsulok. Kung ang haba ng isa sa mga gilid ay alam, ang dalawa pang gilid ay matutukoy. Sa kanang larawan, ipinapakita ang rasyo ng mga punsiyon na trigonometriko ng isang tatsulok kung saan ang anggulong A ay alam, at ang ang a, b at c ay tumutukoy sa haba ng mga gilid nito.

sine gilis

sin

A

=

kabaligtaran(opposite)

haypotenus(hypotenuse)

=

a

c

.

{\displaystyle \sin A={\frac {\textrm {kabaligtaran(opposite)}}{\textrm {haypotenus(hypotenuse)}}}={\frac {a}{\,c\,}}\,.}

cosine

cos

A

=

katabi(adjacent)

haypotenus(hypotenuse)

=

b

c

.

{\displaystyle \cos A={\frac {\textrm {katabi(adjacent)}}{\textrm {haypotenus(hypotenuse)}}}={\frac {b}{\,c\,}}\,.}

tangent

tan

A

=

kabaligtaran(opposite)

katabi(adjacent)

=

a

b

=

sin

A

cos

A

.

{\displaystyle \tan A={\frac {\textrm {kabaligtaran(opposite)}}{\textrm {katabi(adjacent)}}}={\frac {a}{\,b\,}}={\frac {\sin A}{\cos A}}\,.}

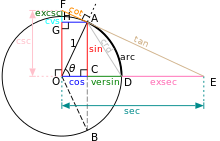

Ang mga depinisyon sa itaas ay inalalapat sa mga anggulo sa pagitan ng 0 at 90 digri (0 at π/2 radians ) lamang. Kung gagamitin ang bilog na unit (unit circle), maaaring palawigin ang mga ito sa lahat ng positibo at negatibong argumento. Ang mga punsiyong trigonometriko ay periodiko na may period na 360 digi o 2π radians. Ang ibig sabihin nito, ang mga halaga nito ay umuulit sa mga interbal na ito. Ang tangent at cotangent ay may mas maikling period na 180 digri o π radian.

Ang mga punsiyong trigonometriko ay maaaring ilarawan sa ibang paraan bukod sa mga heometrikal na depinisyon sa itaas gamit ang mga kasangkapan sa kalkulo at inpinidong serye . Sa mga depinisyong ito, ang mga punsiyong trigonometriko ay maaaring ilarawan para sa mga bilang na kompleks . Ang eksponensiyal na kompleks na punsiyon ay partikular na magagamit.

e

x

+

i

y

=

e

x

(

cos

y

+

i

sin

y

)

.

{\displaystyle e^{x+iy}=e^{x}(\cos y+i\sin y).}

Proseso ng pagga-

grapo ng

y = sin(

x ) gamit ang bilog na unit.

Proseso ng pagga-

grapo ng

y = tan(

x ) gamit ang bilog na unit.

Proseso ng pagga-

grapo ng

y = csc(

x ) gamit ang bilog na unit.

Ang Inbersong (kabaligtarang) trigonometrikong mga punsiyon (inverse trigonometric functions o cyclometric functions) ang mga inberso (kabaligtaran) ng mga punsiyong trigonometriko na nagbibigay ng anggulo ng tatsulok. Kung paanong ang inberso ng ugat ng kwadrado (square root)

y

=

x

{\displaystyle y={\sqrt {x}}}

kwadrado (square) y 2 = x , ang inberso ng

sin

(

θ

)

=

x

{\displaystyle \sin(\theta )=x}

arcsin

(

x

)

=

θ

{\displaystyle \arcsin(x)=\theta }

Θ ay kumakatawan sa isang anggulo ng tatsulok.

Ang tatlong karaniwang notasyon ng mga inbersyong punsiyong trigonometriko ay:

Sin

−

1

x

=

θ

,

arcsin

x

=

θ

,

asin

x

=

θ

{\displaystyle \displaystyle {\mbox{Sin}}^{-1}x=\theta ,\arcsin x=\theta ,{\mbox{asin}}x=\theta }

Cos

−

1

x

=

θ

,

arccos

x

=

θ

,

acos

x

=

θ

{\displaystyle \displaystyle {\mbox{Cos}}^{-1}x=\theta ,\arccos x=\theta ,{\mbox{acos}}x=\theta }

Tan

−

1

x

=

θ

,

arctan

x

=

θ

,

atan

x

=

θ

{\displaystyle \displaystyle {\mbox{Tan}}^{-1}x=\theta ,\arctan x=\theta ,{\mbox{atan}}x=\theta }

Maraming halaga ang ibinibigay ng sin(y) = x; halimbawa, ang sin(0) = 0, pati na rin ang sin(π) = 0, sin(2π) = 0, at iba pa. Samakatuwid ang punsiyong arcsine ay nagbibigay rin ng maraming halaga: arcsin(0) = 0, pati na rin arcsin(0) = π, arcsin(0) = 2π, at iba pa. Kung isang halaga lang ang ninanais, ang punsiyon ay hihigpitan lamang sa prinsipal na sangay. Sa restriksiyong ito, sa bawat x sa sakop (domain) ng ekspresyong arcsin(x), ito ay magdudulot lamang ng isang halaga na tinatawag na prinsipal na halaga. Ang katangiang ito ay lumalapat sa lahat ng inbersong punsiyong trigonometriko. Ang mga prinsipal na inberso ay nakatala sa sumusunod na tabla:

Pangalan

Usual na notasyon

Depinisyon

Sakop (domain) ng x sa real na resulta

Range sa karaniwang prinsipal na halaga radian )

Range sa karaniwang prinsipal na halaga digri )

arcsine y = arcsin x x = sin y −1 ≤ x ≤ 1

−π/2 ≤ y ≤ π/2

−90° ≤ y ≤ 90°

arccosine y = arccos x x = cos y −1 ≤ x ≤ 1

0 ≤ y ≤ π

0° ≤ y ≤ 180°

arctangent y = arctan x x = tan y all real numbers

−π/2 < y < π/2

−90° < y < 90°

arccotangent y = arccot x x = cot y all real numbers

0 < y < π

0° < y < 180°

arcsecant y = arcsec x x = sec y x ≤ −1 or 1 ≤ x 0 ≤ y < π/2 or π/2 < y ≤ π

0° ≤ y < 90° or 90° < y ≤ 180°

arccosecant y = arccsc x x = csc y x ≤ −1 or 1 ≤ x −π/2 ≤ y < 0 or 0 < y ≤ π/2

-90° ≤ y < 0° or 0° < y ≤ 90°

Ikaw ay nakatayo na may layong 20 talampakan mula sa paanan ng isang puno at nasukat mo ang anggulo ng elebasyon na 38 digri gamit ang isang instrumento (halimbawa clinometer o theodolite). Nais mong malaman ang taas ng puno ng hindi mo pisikal na susukatin ito.

Ang solusyon ay depende sa iyong taas habang sinusukat mo ang anggulo ng elebasyon mula sa linya ng paningin. Ipagpalagay nating ikaw ay may taas na 5 talampakan.

Ang larawan na ito ay nagpapakita ng tatsulok na ating nilulutas Ang larawan sa kanan ay nagpapakita na pag nalaman na ang halaga ng T , kailangang magdagdag ng 5 talampakan sa halagang ito upang malaman ang kabuuang taas ng isang tatsulok. Upang malaman ang T kailangan nating gamitin ang punsiyong tangent:

tan

(

38

∘

)

=

{\displaystyle \tan(38^{\circ })=\,\!}

kabaligtaran (opposite)

katabi (adjacent)

=

T

20

{\displaystyle {\frac {\text{kabaligtaran (opposite)}}{\text{katabi (adjacent)}}}={\frac {T}{20}}}

tan

(

38

∘

)

=

{\displaystyle \tan(38^{\circ })=\,\!}

T

20

{\displaystyle {\frac {T}{20}}}

T

=

{\displaystyle T=\,\!}

20

tan

(

38

∘

)

≈

15.63

{\displaystyle 20\tan(38^{\circ })\approx 15.63\,\!}

taas ng puno

≈

{\displaystyle {\text{taas ng puno}}\approx \,\!}

20.63

talampakan

{\displaystyle 20.63\ {\text{talampakan}}\,\!}

Ang mundo, buwan at araw ay lumikha ng tamang tatsulok (right triangle) sa unang kwarter ng buwan. Ang layo ng mundo mula sa buwan ay 240,002.5 milya. Ano ang distansiya sa pagitan ng araw at buwan?

Gamitin natin ang d bilang distansiya sa pagitan ng araw at buwan. Maaari nating gamitin ang punsiyong tangent upang matukoy ang halaga ng d :

tan

(

89.85

∘

)

=

{\displaystyle \tan(89.85^{\circ })=\,\!}

d

240

,

002.5

{\displaystyle {\frac {d}{240,002.5}}}

d

i

s

t

a

n

s

i

y

a

=

{\displaystyle distansiya=\,\!}

240

,

002.5

tan

(

89.85

∘

)

=

91

,

673

,

992.71

milya

{\displaystyle 240,002.5\tan(89.85^{\circ })=91,673,992.71\ {\text{milya}}}

Ang identidad na trigonometriko ay tumutukoy sa mga ekwalidad (pagiging magkatumbas) ng mga ekspresyon ng mga punsiyon na trigonometriko na palaging totoo sa anumang halaga ng mga input gaya ng Θ at π na kumakatawan sa mga anggulo ng tatsulok. Halimbawa, sa anumang ibinigay na halaga ng Θ , ang resulta ng ekspresyong

sec

θ

{\displaystyle \sec \theta }

1

cos

θ

{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{\cos \theta }}}

identidad na trigonometriko ay ginagamit din upang lutasin/pasimplehin ang mga ekwasyon na trigonometriko sa termino ng isang punsiyon trigonometriko.

Mga resiprokal ng cosine, sine, at tangent:

sec

θ

=

1

cos

θ

,

csc

θ

=

1

sin

θ

,

cot

θ

=

1

tan

θ

=

cos

θ

sin

θ

.

{\displaystyle \sec \theta ={\frac {1}{\cos \theta }},\quad \csc \theta ={\frac {1}{\sin \theta }},\quad \cot \theta ={\frac {1}{\tan \theta }}={\frac {\cos \theta }{\sin \theta }}.}

Reflected in

θ

=

0

{\displaystyle \theta =0}

[ 3]

Reflected in

θ

=

π

/

4

{\displaystyle \theta =\pi /4}

[ 4]

Reflected in

θ

=

π

/

2

{\displaystyle \theta =\pi /2}

sin

(

−

θ

)

=

−

sin

θ

cos

(

−

θ

)

=

+

cos

θ

tan

(

−

θ

)

=

−

tan

θ

csc

(

−

θ

)

=

−

csc

θ

sec

(

−

θ

)

=

+

sec

θ

cot

(

−

θ

)

=

−

cot

θ

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\sin(-\theta )&=-\sin \theta \\\cos(-\theta )&=+\cos \theta \\\tan(-\theta )&=-\tan \theta \\\csc(-\theta )&=-\csc \theta \\\sec(-\theta )&=+\sec \theta \\\cot(-\theta )&=-\cot \theta \end{aligned}}}

sin

(

π

2

−

θ

)

=

+

cos

θ

cos

(

π

2

−

θ

)

=

+

sin

θ

tan

(

π

2

−

θ

)

=

+

cot

θ

csc

(

π

2

−

θ

)

=

+

sec

θ

sec

(

π

2

−

θ

)

=

+

csc

θ

cot

(

π

2

−

θ

)

=

+

tan

θ

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\sin({\tfrac {\pi }{2}}-\theta )&=+\cos \theta \\\cos({\tfrac {\pi }{2}}-\theta )&=+\sin \theta \\\tan({\tfrac {\pi }{2}}-\theta )&=+\cot \theta \\\csc({\tfrac {\pi }{2}}-\theta )&=+\sec \theta \\\sec({\tfrac {\pi }{2}}-\theta )&=+\csc \theta \\\cot({\tfrac {\pi }{2}}-\theta )&=+\tan \theta \end{aligned}}}

sin

(

π

−

θ

)

=

+

sin

θ

cos

(

π

−

θ

)

=

−

cos

θ

tan

(

π

−

θ

)

=

−

tan

θ

csc

(

π

−

θ

)

=

+

csc

θ

sec

(

π

−

θ

)

=

−

sec

θ

cot

(

π

−

θ

)

=

−

cot

θ

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\sin(\pi -\theta )&=+\sin \theta \\\cos(\pi -\theta )&=-\cos \theta \\\tan(\pi -\theta )&=-\tan \theta \\\csc(\pi -\theta )&=+\csc \theta \\\sec(\pi -\theta )&=-\sec \theta \\\cot(\pi -\theta )&=-\cot \theta \\\end{aligned}}}

Shift by π/2

Shift by π [ 5]

Shift by 2π [ 6]

sin

(

θ

+

π

2

)

=

+

cos

θ

cos

(

θ

+

π

2

)

=

−

sin

θ

tan

(

θ

+

π

2

)

=

−

cot

θ

csc

(

θ

+

π

2

)

=

+

sec

θ

sec

(

θ

+

π

2

)

=

−

csc

θ

cot

(

θ

+

π

2

)

=

−

tan

θ

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\sin(\theta +{\tfrac {\pi }{2}})&=+\cos \theta \\\cos(\theta +{\tfrac {\pi }{2}})&=-\sin \theta \\\tan(\theta +{\tfrac {\pi }{2}})&=-\cot \theta \\\csc(\theta +{\tfrac {\pi }{2}})&=+\sec \theta \\\sec(\theta +{\tfrac {\pi }{2}})&=-\csc \theta \\\cot(\theta +{\tfrac {\pi }{2}})&=-\tan \theta \end{aligned}}}

sin

(

θ

+

π

)

=

−

sin

θ

cos

(

θ

+

π

)

=

−

cos

θ

tan

(

θ

+

π

)

=

+

tan

θ

csc

(

θ

+

π

)

=

−

csc

θ

sec

(

θ

+

π

)

=

−

sec

θ

cot

(

θ

+

π

)

=

+

cot

θ

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\sin(\theta +\pi )&=-\sin \theta \\\cos(\theta +\pi )&=-\cos \theta \\\tan(\theta +\pi )&=+\tan \theta \\\csc(\theta +\pi )&=-\csc \theta \\\sec(\theta +\pi )&=-\sec \theta \\\cot(\theta +\pi )&=+\cot \theta \\\end{aligned}}}

sin

(

θ

+

2

π

)

=

+

sin

θ

cos

(

θ

+

2

π

)

=

+

cos

θ

tan

(

θ

+

2

π

)

=

+

tan

θ

csc

(

θ

+

2

π

)

=

+

csc

θ

sec

(

θ

+

2

π

)

=

+

sec

θ

cot

(

θ

+

2

π

)

=

+

cot

θ

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\sin(\theta +2\pi )&=+\sin \theta \\\cos(\theta +2\pi )&=+\cos \theta \\\tan(\theta +2\pi )&=+\tan \theta \\\csc(\theta +2\pi )&=+\csc \theta \\\sec(\theta +2\pi )&=+\sec \theta \\\cot(\theta +2\pi )&=+\cot \theta \end{aligned}}}

sin

(

∑

i

=

1

∞

θ

i

)

=

∑

odd

k

≥

1

(

−

1

)

(

k

−

1

)

/

2

∑

A

⊆

{

1

,

2

,

3

,

…

}

|

A

|

=

k

(

∏

i

∈

A

sin

θ

i

∏

i

∉

A

cos

θ

i

)

{\displaystyle \sin \left(\sum _{i=1}^{\infty }\theta _{i}\right)=\sum _{{\text{odd}}\ k\geq 1}(-1)^{(k-1)/2}\sum _{\begin{smallmatrix}A\subseteq \{\,1,2,3,\dots \,\}\\\left|A\right|=k\end{smallmatrix}}\left(\prod _{i\in A}\sin \theta _{i}\prod _{i\not \in A}\cos \theta _{i}\right)}

cos

(

∑

i

=

1

∞

θ

i

)

=

∑

even

k

≥

0

(

−

1

)

k

/

2

∑

A

⊆

{

1

,

2

,

3

,

…

}

|

A

|

=

k

(

∏

i

∈

A

sin

θ

i

∏

i

∉

A

cos

θ

i

)

{\displaystyle \cos \left(\sum _{i=1}^{\infty }\theta _{i}\right)=\sum _{{\text{even}}\ k\geq 0}~(-1)^{k/2}~~\sum _{\begin{smallmatrix}A\subseteq \{\,1,2,3,\dots \,\}\\\left|A\right|=k\end{smallmatrix}}\left(\prod _{i\in A}\sin \theta _{i}\prod _{i\not \in A}\cos \theta _{i}\right)}

e

0

=

1

e

1

=

∑

1

≤

i

≤

n

x

i

=

∑

1

≤

i

≤

n

tan

θ

i

e

2

=

∑

1

≤

i

<

j

≤

n

x

i

x

j

=

∑

1

≤

i

<

j

≤

n

tan

θ

i

tan

θ

j

e

3

=

∑

1

≤

i

<

j

<

k

≤

n

x

i

x

j

x

k

=

∑

1

≤

i

<

j

<

k

≤

n

tan

θ

i

tan

θ

j

tan

θ

k

⋮

⋮

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}e_{0}&=1\\[6pt]e_{1}&=\sum _{1\leq i\leq n}x_{i}&&=\sum _{1\leq i\leq n}\tan \theta _{i}\\[6pt]e_{2}&=\sum _{1\leq i<j\leq n}x_{i}x_{j}&&=\sum _{1\leq i<j\leq n}\tan \theta _{i}\tan \theta _{j}\\[6pt]e_{3}&=\sum _{1\leq i<j<k\leq n}x_{i}x_{j}x_{k}&&=\sum _{1\leq i<j<k\leq n}\tan \theta _{i}\tan \theta _{j}\tan \theta _{k}\\&{}\ \ \vdots &&{}\ \ \vdots \end{aligned}}}

sec

(

θ

1

+

⋯

+

θ

n

)

=

sec

θ

1

⋯

sec

θ

n

e

0

−

e

2

+

e

4

−

⋯

csc

(

θ

1

+

⋯

+

θ

n

)

=

sec

θ

1

⋯

sec

θ

n

e

1

−

e

3

+

e

5

−

⋯

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\sec(\theta _{1}+\cdots +\theta _{n})&={\frac {\sec \theta _{1}\cdots \sec \theta _{n}}{e_{0}-e_{2}+e_{4}-\cdots }}\\[8pt]\csc(\theta _{1}+\cdots +\theta _{n})&={\frac {\sec \theta _{1}\cdots \sec \theta _{n}}{e_{1}-e_{3}+e_{5}-\cdots }}\end{aligned}}}

Then

tan

(

θ

1

+

⋯

+

θ

n

)

=

e

1

−

e

3

+

e

5

−

⋯

e

0

−

e

2

+

e

4

−

⋯

,

{\displaystyle \tan(\theta _{1}+\cdots +\theta _{n})={\frac {e_{1}-e_{3}+e_{5}-\cdots }{e_{0}-e_{2}+e_{4}-\cdots }},\!}

Mga katumbas na punsiyon sa termino ng iba pang punsiyon[ 7]

in terms of

sin

θ

{\displaystyle \sin \theta \!}

cos

θ

{\displaystyle \cos \theta \!}

tan

θ

{\displaystyle \tan \theta \!}

csc

θ

{\displaystyle \csc \theta \!}

sec

θ

{\displaystyle \sec \theta \!}

cot

θ

{\displaystyle \cot \theta \!}

sin

θ

=

{\displaystyle \sin \theta =\!}

sin

θ

{\displaystyle \sin \theta \ }

±

1

−

cos

2

θ

{\displaystyle \pm {\sqrt {1-\cos ^{2}\theta }}\!}

±

tan

θ

1

+

tan

2

θ

{\displaystyle \pm {\frac {\tan \theta }{\sqrt {1+\tan ^{2}\theta }}}\!}

1

csc

θ

{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{\csc \theta }}\!}

±

sec

2

θ

−

1

sec

θ

{\displaystyle \pm {\frac {\sqrt {\sec ^{2}\theta -1}}{\sec \theta }}\!}

±

1

1

+

cot

2

θ

{\displaystyle \pm {\frac {1}{\sqrt {1+\cot ^{2}\theta }}}\!}

cos

θ

=

{\displaystyle \cos \theta =\!}

±

1

−

sin

2

θ

{\displaystyle \pm {\sqrt {1-\sin ^{2}\theta }}\!}

cos

θ

{\displaystyle \cos \theta \!}

±

1

1

+

tan

2

θ

{\displaystyle \pm {\frac {1}{\sqrt {1+\tan ^{2}\theta }}}\!}

±

csc

2

θ

−

1

csc

θ

{\displaystyle \pm {\frac {\sqrt {\csc ^{2}\theta -1}}{\csc \theta }}\!}

1

sec

θ

{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{\sec \theta }}\!}

±

cot

θ

1

+

cot

2

θ

{\displaystyle \pm {\frac {\cot \theta }{\sqrt {1+\cot ^{2}\theta }}}\!}

tan

θ

=

{\displaystyle \tan \theta =\!}

±

sin

θ

1

−

sin

2

θ

{\displaystyle \pm {\frac {\sin \theta }{\sqrt {1-\sin ^{2}\theta }}}\!}

±

1

−

cos

2

θ

cos

θ

{\displaystyle \pm {\frac {\sqrt {1-\cos ^{2}\theta }}{\cos \theta }}\!}

tan

θ

{\displaystyle \tan \theta \!}

±

1

csc

2

θ

−

1

{\displaystyle \pm {\frac {1}{\sqrt {\csc ^{2}\theta -1}}}\!}

±

sec

2

θ

−

1

{\displaystyle \pm {\sqrt {\sec ^{2}\theta -1}}\!}

1

cot

θ

{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{\cot \theta }}\!}

csc

θ

=

{\displaystyle \csc \theta =\!}

1

sin

θ

{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{\sin \theta }}\!}

±

1

1

−

cos

2

θ

{\displaystyle \pm {\frac {1}{\sqrt {1-\cos ^{2}\theta }}}\!}

±

1

+

tan

2

θ

tan

θ

{\displaystyle \pm {\frac {\sqrt {1+\tan ^{2}\theta }}{\tan \theta }}\!}

csc

θ

{\displaystyle \csc \theta \!}

±

sec

θ

sec

2

θ

−

1

{\displaystyle \pm {\frac {\sec \theta }{\sqrt {\sec ^{2}\theta -1}}}\!}

±

1

+

cot

2

θ

{\displaystyle \pm {\sqrt {1+\cot ^{2}\theta }}\!}

sec

θ

=

{\displaystyle \sec \theta =\!}

±

1

1

−

sin

2

θ

{\displaystyle \pm {\frac {1}{\sqrt {1-\sin ^{2}\theta }}}\!}

1

cos

θ

{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{\cos \theta }}\!}

±

1

+

tan

2

θ

{\displaystyle \pm {\sqrt {1+\tan ^{2}\theta }}\!}

±

csc

θ

csc

2

θ

−

1

{\displaystyle \pm {\frac {\csc \theta }{\sqrt {\csc ^{2}\theta -1}}}\!}

sec

θ

{\displaystyle \sec \theta \!}

±

1

+

cot

2

θ

cot

θ

{\displaystyle \pm {\frac {\sqrt {1+\cot ^{2}\theta }}{\cot \theta }}\!}

cot

θ

=

{\displaystyle \cot \theta =\!}

±

1

−

sin

2

θ

sin

θ

{\displaystyle \pm {\frac {\sqrt {1-\sin ^{2}\theta }}{\sin \theta }}\!}

±

cos

θ

1

−

cos

2

θ

{\displaystyle \pm {\frac {\cos \theta }{\sqrt {1-\cos ^{2}\theta }}}\!}

1

tan

θ

{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{\tan \theta }}\!}

±

csc

2

θ

−

1

{\displaystyle \pm {\sqrt {\csc ^{2}\theta -1}}\!}

±

1

sec

2

θ

−

1

{\displaystyle \pm {\frac {1}{\sqrt {\sec ^{2}\theta -1}}}\!}

cot

θ

{\displaystyle \cot \theta \!}

sin

2

A

+

cos

2

A

=

1

{\displaystyle \sin ^{2}A+\cos ^{2}A=1\ }

sec

2

A

−

tan

2

A

=

1

{\displaystyle \sec ^{2}A-\tan ^{2}A=1\ }

csc

2

A

−

cot

2

A

=

1

{\displaystyle \csc ^{2}A-\cot ^{2}A=1\ }

Sine

sin

(

α

±

β

)

=

sin

α

cos

β

±

cos

α

sin

β

{\displaystyle \sin(\alpha \pm \beta )=\sin \alpha \cos \beta \pm \cos \alpha \sin \beta \!}

[ 8] [ 9]

Cosine

cos

(

α

±

β

)

=

cos

α

cos

β

∓

sin

α

sin

β

{\displaystyle \cos(\alpha \pm \beta )=\cos \alpha \cos \beta \mp \sin \alpha \sin \beta \,}

[ 9] [ 10]

Tangent

tan

(

α

±

β

)

=

tan

α

±

tan

β

1

∓

tan

α

tan

β

{\displaystyle \tan(\alpha \pm \beta )={\frac {\tan \alpha \pm \tan \beta }{1\mp \tan \alpha \tan \beta }}}

[ 9] [ 11]

Arcsine

arcsin

α

±

arcsin

β

=

arcsin

(

α

1

−

β

2

±

β

1

−

α

2

)

{\displaystyle \arcsin \alpha \pm \arcsin \beta =\arcsin(\alpha {\sqrt {1-\beta ^{2}}}\pm \beta {\sqrt {1-\alpha ^{2}}})}

[ 12]

Arccosine

arccos

α

±

arccos

β

=

arccos

(

α

β

∓

(

1

−

α

2

)

(

1

−

β

2

)

)

{\displaystyle \arccos \alpha \pm \arccos \beta =\arccos(\alpha \beta \mp {\sqrt {(1-\alpha ^{2})(1-\beta ^{2})}})}

[ 13]

Arctangent

arctan

α

±

arctan

β

=

arctan

(

α

±

β

1

∓

α

β

)

{\displaystyle \arctan \alpha \pm \arctan \beta =\arctan \left({\frac {\alpha \pm \beta }{1\mp \alpha \beta }}\right)}

[ 14]

Doble-anggulo[ 15] [ 16]

sin

2

θ

=

2

sin

θ

cos

θ

=

2

tan

θ

1

+

tan

2

θ

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\sin 2\theta &=2\sin \theta \cos \theta \ \\&={\frac {2\tan \theta }{1+\tan ^{2}\theta }}\end{aligned}}}

cos

2

θ

=

cos

2

θ

−

sin

2

θ

=

2

cos

2

θ

−

1

=

1

−

2

sin

2

θ

=

1

−

tan

2

θ

1

+

tan

2

θ

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\cos 2\theta &=\cos ^{2}\theta -\sin ^{2}\theta \\&=2\cos ^{2}\theta -1\\&=1-2\sin ^{2}\theta \\&={\frac {1-\tan ^{2}\theta }{1+\tan ^{2}\theta }}\end{aligned}}}

tan

2

θ

=

2

tan

θ

1

−

tan

2

θ

{\displaystyle \tan 2\theta ={\frac {2\tan \theta }{1-\tan ^{2}\theta }}\!}

cot

2

θ

=

cot

2

θ

−

1

2

cot

θ

{\displaystyle \cot 2\theta ={\frac {\cot ^{2}\theta -1}{2\cot \theta }}\!}

Triple-anggulo[ 17] [ 18]

sin

3

θ

=

3

cos

2

θ

sin

θ

−

sin

3

θ

=

3

sin

θ

−

4

sin

3

θ

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\sin 3\theta &=3\cos ^{2}\theta \sin \theta -\sin ^{3}\theta \\&=3\sin \theta -4\sin ^{3}\theta \end{aligned}}}

cos

3

θ

=

cos

3

θ

−

3

sin

2

θ

cos

θ

=

4

cos

3

θ

−

3

cos

θ

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\cos 3\theta &=\cos ^{3}\theta -3\sin ^{2}\theta \cos \theta \\&=4\cos ^{3}\theta -3\cos \theta \end{aligned}}}

tan

3

θ

=

3

tan

θ

−

tan

3

θ

1

−

3

tan

2

θ

{\displaystyle \tan 3\theta ={\frac {3\tan \theta -\tan ^{3}\theta }{1-3\tan ^{2}\theta }}\!}

cot

3

θ

=

3

cot

θ

−

cot

3

θ

1

−

3

cot

2

θ

{\displaystyle \cot 3\theta ={\frac {3\cot \theta -\cot ^{3}\theta }{1-3\cot ^{2}\theta }}\!}

Kalahating-anggulo[ 19] [ 20]

sin

θ

2

=

±

1

−

cos

θ

2

{\displaystyle \sin {\frac {\theta }{2}}=\pm \,{\sqrt {\frac {1-\cos \theta }{2}}}}

cos

θ

2

=

±

1

+

cos

θ

2

{\displaystyle \cos {\frac {\theta }{2}}=\pm \,{\sqrt {\frac {1+\cos \theta }{2}}}}

tan

θ

2

=

csc

θ

−

cot

θ

=

±

1

−

cos

θ

1

+

cos

θ

=

sin

θ

1

+

cos

θ

=

1

−

cos

θ

sin

θ

tan

η

+

θ

2

=

sin

η

+

sin

θ

cos

η

+

cos

θ

tan

(

θ

2

+

π

4

)

=

sec

θ

+

tan

θ

1

−

sin

θ

1

+

sin

θ

=

1

−

tan

(

θ

/

2

)

1

+

tan

(

θ

/

2

)

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\tan {\frac {\theta }{2}}&=\csc \theta -\cot \theta \\&=\pm \,{\sqrt {1-\cos \theta \over 1+\cos \theta }}\\[8pt]&={\frac {\sin \theta }{1+\cos \theta }}\\[8pt]&={\frac {1-\cos \theta }{\sin \theta }}\\[10pt]\tan {\frac {\eta +\theta }{2}}&={\frac {\sin \eta +\sin \theta }{\cos \eta +\cos \theta }}\\[8pt]\tan \left({\frac {\theta }{2}}+{\frac {\pi }{4}}\right)&=\sec \theta +\tan \theta \\[8pt]{\sqrt {\frac {1-\sin \theta }{1+\sin \theta }}}&={\frac {1-\tan(\theta /2)}{1+\tan(\theta /2)}}\end{aligned}}}

cot

θ

2

=

csc

θ

+

cot

θ

=

±

1

+

cos

θ

1

−

cos

θ

=

sin

θ

1

−

cos

θ

=

1

+

cos

θ

sin

θ

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\cot {\frac {\theta }{2}}&=\csc \theta +\cot \theta \\&=\pm \,{\sqrt {1+\cos \theta \over 1-\cos \theta }}\\[8pt]&={\frac {\sin \theta }{1-\cos \theta }}\\[8pt]&={\frac {1+\cos \theta }{\sin \theta }}\end{aligned}}}

Sine

Cosine

Other

sin

2

θ

=

1

−

cos

2

θ

2

{\displaystyle \sin ^{2}\theta ={\frac {1-\cos 2\theta }{2}}\!}

cos

2

θ

=

1

+

cos

2

θ

2

{\displaystyle \cos ^{2}\theta ={\frac {1+\cos 2\theta }{2}}\!}

sin

2

θ

cos

2

θ

=

1

−

cos

4

θ

8

{\displaystyle \sin ^{2}\theta \cos ^{2}\theta ={\frac {1-\cos 4\theta }{8}}\!}

sin

3

θ

=

3

sin

θ

−

sin

3

θ

4

{\displaystyle \sin ^{3}\theta ={\frac {3\sin \theta -\sin 3\theta }{4}}\!}

cos

3

θ

=

3

cos

θ

+

cos

3

θ

4

{\displaystyle \cos ^{3}\theta ={\frac {3\cos \theta +\cos 3\theta }{4}}\!}

sin

3

θ

cos

3

θ

=

3

sin

2

θ

−

sin

6

θ

32

{\displaystyle \sin ^{3}\theta \cos ^{3}\theta ={\frac {3\sin 2\theta -\sin 6\theta }{32}}\!}

sin

4

θ

=

3

−

4

cos

2

θ

+

cos

4

θ

8

{\displaystyle \sin ^{4}\theta ={\frac {3-4\cos 2\theta +\cos 4\theta }{8}}\!}

cos

4

θ

=

3

+

4

cos

2

θ

+

cos

4

θ

8

{\displaystyle \cos ^{4}\theta ={\frac {3+4\cos 2\theta +\cos 4\theta }{8}}\!}

sin

4

θ

cos

4

θ

=

3

−

4

cos

4

θ

+

cos

8

θ

128

{\displaystyle \sin ^{4}\theta \cos ^{4}\theta ={\frac {3-4\cos 4\theta +\cos 8\theta }{128}}\!}

sin

5

θ

=

10

sin

θ

−

5

sin

3

θ

+

sin

5

θ

16

{\displaystyle \sin ^{5}\theta ={\frac {10\sin \theta -5\sin 3\theta +\sin 5\theta }{16}}\!}

cos

5

θ

=

10

cos

θ

+

5

cos

3

θ

+

cos

5

θ

16

{\displaystyle \cos ^{5}\theta ={\frac {10\cos \theta +5\cos 3\theta +\cos 5\theta }{16}}\!}

sin

5

θ

cos

5

θ

=

10

sin

2

θ

−

5

sin

6

θ

+

sin

10

θ

512

{\displaystyle \sin ^{5}\theta \cos ^{5}\theta ={\frac {10\sin 2\theta -5\sin 6\theta +\sin 10\theta }{512}}\!}

Cosine

Sine

if

n

is odd

{\displaystyle {\text{if }}n{\text{ is odd}}}

cos

n

θ

=

2

2

n

∑

k

=

0

n

−

1

2

(

n

k

)

cos

(

(

n

−

2

k

)

θ

)

{\displaystyle \cos ^{n}\theta ={\frac {2}{2^{n}}}\sum _{k=0}^{\frac {n-1}{2}}{\binom {n}{k}}\cos {((n-2k)\theta )}}

sin

n

θ

=

2

2

n

∑

k

=

0

n

−

1

2

(

−

1

)

(

n

−

1

2

−

k

)

(

n

k

)

sin

(

(

n

−

2

k

)

θ

)

{\displaystyle \sin ^{n}\theta ={\frac {2}{2^{n}}}\sum _{k=0}^{\frac {n-1}{2}}(-1)^{({\frac {n-1}{2}}-k)}{\binom {n}{k}}\sin {((n-2k)\theta )}}

if

n

is even

{\displaystyle {\text{if }}n{\text{ is even}}}

cos

n

θ

=

1

2

n

(

n

n

2

)

+

2

2

n

∑

k

=

0

n

2

−

1

(

n

k

)

cos

(

(

n

−

2

k

)

θ

)

{\displaystyle \cos ^{n}\theta ={\frac {1}{2^{n}}}{\binom {n}{\frac {n}{2}}}+{\frac {2}{2^{n}}}\sum _{k=0}^{{\frac {n}{2}}-1}{\binom {n}{k}}\cos {((n-2k)\theta )}}

sin

n

θ

=

1

2

n

(

n

n

2

)

+

2

2

n

∑

k

=

0

n

2

−

1

(

−

1

)

(

n

2

−

k

)

(

n

k

)

cos

(

(

n

−

2

k

)

θ

)

{\displaystyle \sin ^{n}\theta ={\frac {1}{2^{n}}}{\binom {n}{\frac {n}{2}}}+{\frac {2}{2^{n}}}\sum _{k=0}^{{\frac {n}{2}}-1}(-1)^{({\frac {n}{2}}-k)}{\binom {n}{k}}\cos {((n-2k)\theta )}}

Product-to-sum[ 21]

cos

θ

cos

φ

=

cos

(

θ

−

φ

)

+

cos

(

θ

+

φ

)

2

{\displaystyle \cos \theta \cos \varphi ={\cos(\theta -\varphi )+\cos(\theta +\varphi ) \over 2}}

sin

θ

sin

φ

=

cos

(

θ

−

φ

)

−

cos

(

θ

+

φ

)

2

{\displaystyle \sin \theta \sin \varphi ={\cos(\theta -\varphi )-\cos(\theta +\varphi ) \over 2}}

sin

θ

cos

φ

=

sin

(

θ

+

φ

)

+

sin

(

θ

−

φ

)

2

{\displaystyle \sin \theta \cos \varphi ={\sin(\theta +\varphi )+\sin(\theta -\varphi ) \over 2}}

cos

θ

sin

φ

=

sin

(

θ

+

φ

)

−

sin

(

θ

−

φ

)

2

{\displaystyle \cos \theta \sin \varphi ={\sin(\theta +\varphi )-\sin(\theta -\varphi ) \over 2}}

Sum-to-product[ 22]

sin

θ

±

sin

φ

=

2

sin

(

θ

±

φ

2

)

cos

(

θ

∓

φ

2

)

{\displaystyle \sin \theta \pm \sin \varphi =2\sin \left({\frac {\theta \pm \varphi }{2}}\right)\cos \left({\frac {\theta \mp \varphi }{2}}\right)}

cos

θ

+

cos

φ

=

2

cos

(

θ

+

φ

2

)

cos

(

θ

−

φ

2

)

{\displaystyle \cos \theta +\cos \varphi =2\cos \left({\frac {\theta +\varphi }{2}}\right)\cos \left({\frac {\theta -\varphi }{2}}\right)}

cos

θ

−

cos

φ

=

−

2

sin

(

θ

+

φ

2

)

sin

(

θ

−

φ

2

)

{\displaystyle \cos \theta -\cos \varphi =-2\sin \left({\theta +\varphi \over 2}\right)\sin \left({\theta -\varphi \over 2}\right)}

Ang pormula ni Euler na nagsasaad na

e

i

x

=

cos

x

+

i

sin

x

{\displaystyle e^{ix}=\cos x+i\sin x}

e imahinaryong unit na i :

sin

x

=

e

i

x

−

e

−

i

x

2

i

,

cos

x

=

e

i

x

+

e

−

i

x

2

,

tan

x

=

i

(

e

−

i

x

−

e

i

x

)

e

i

x

+

e

−

i

x

.

{\displaystyle \sin x={\frac {e^{ix}-e^{-ix}}{2i}},\qquad \cos x={\frac {e^{ix}+e^{-ix}}{2}},\qquad \tan x={\frac {i(e^{-ix}-e^{ix})}{e^{ix}+e^{-ix}}}.}

Ang mga anggulong α , β , at γ ay kabalagitaran ng mga gilid na a , b , and c . Ang batas ng mga sine (law of sines) ay ginagamit upang kwentahin ang mga natitirang gilid kung ang dalawang anggulo at isang gilid ay alam. Ito ay ginagamit rin kung ang dalawang gilid at ang anggulo sa pagitan nito ay alam. Sa ibang kaso, ang pormula ay nagbibigay ng dalawang posibleng halaga sa anggulo sa pagitan ng dalawang gilid.

a

sin

α

=

b

sin

β

=

c

sin

γ

=

2

R

,

{\displaystyle {\frac {a}{\sin \alpha \ }}={\frac {b}{\sin \beta \ }}={\frac {c}{\sin \gamma \ }}=2R,}

kung saan ang R ang radyus ng bilog na sirkumskribo (bilog na dumadaan sa lahat ng berteks ng isang tatsulok):

R

=

a

b

c

(

a

+

b

+

c

)

(

a

−

b

+

c

)

(

a

+

b

−

c

)

(

b

+

c

−

a

)

.

{\displaystyle R={\frac {abc}{\sqrt {(a+b+c)(a-b+c)(a+b-c)(b+c-a)}}}.}

Isa pang batas kaugnay ng sine ay maaaring gamitin upang kwentahin ang isang area ng isang tatsulok. Kung ang dalawang mga gilid at isang anggulo sa pagitan ng mga gilid na ito ay ibinigay, ang area ng tatsulok ay:

Area

=

1

2

a

b

sin

C

.

{\displaystyle {\mbox{Area}}={\frac {1}{2}}ab\sin C.}

Lahat ng mga punsiyong trigonometriko ng isang anggulong tinatawag na θ ay maaaring likhain sa termino ng isang bilog na unit (unit circle) sa O . Ang batas ng mga cosine (law of cosines) ay isang ektensiyon ng Teorema ni Pitagoras sa anumang napiling sukat na tatsulok. Ang batas ng cosine ay ginagamit upang malaman ang ikatlong gilid kung ang dalawang gilid at ang ang anggulo sa pagitan ng dalawang gilid na ito ay alam.

c

2

=

a

2

+

b

2

−

2

a

b

cos

γ

{\displaystyle c^{2}=a^{2}+b^{2}-2ab\cos \gamma \,}

a

2

=

b

2

+

c

2

−

2

b

c

cos

α

{\displaystyle a^{2}=b^{2}+c^{2}-2bc\cos \alpha \,}

b

2

=

a

2

+

c

2

−

2

a

c

cos

β

{\displaystyle b^{2}=a^{2}+c^{2}-2ac\cos \beta \,}

Ang inibang anyo ng batas ng cosine ay ginagamit upang malaman ang mga anggulo ng isang tatsulok kung ang lahat ng gilid nito ay alam.

cos

γ

=

a

2

+

b

2

−

c

2

2

a

b

{\displaystyle \cos \gamma \ ={\frac {a^{2}+b^{2}-c^{2}}{2ab}}\,}

cos

α

=

b

2

+

c

2

−

a

2

2

b

c

{\displaystyle \cos \alpha \ ={\frac {b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}}{2bc}}\,}

cos

β

=

c

2

+

a

2

−

b

2

2

c

a

{\displaystyle \cos \beta \ ={\frac {c^{2}+a^{2}-b^{2}}{2ca}}\,}

Ang batas ng mga tangent (law of tangents) ay maaaring gamitin upang matukoy ang isang gilid o anggulo kung ang dalawang gilid at isang anggulo na hindi kasama o dalawang anggulo at isang gilid ay alam.

a

−

b

a

+

b

=

tan

[

1

2

(

A

−

B

)

]

tan

[

1

2

(

A

+

B

)

]

{\displaystyle {\frac {a-b}{a+b}}={\frac {\tan \left[{\tfrac {1}{2}}(A-B)\right]}{\tan \left[{\tfrac {1}{2}}(A+B)\right]}}}

Para lutasin ang bariabulo na x sa ekwasyong nasa anyong

a

sin

x

+

b

cos

x

=

c

{\displaystyle a\sin x+b\cos x=c}

konstante , gagamit tayo ng identidad na trigonometriko na:

a

sin

x

+

b

cos

x

=

a

2

+

b

2

sin

(

x

+

α

)

{\displaystyle a\sin x+b\cos x={\sqrt {a^{2}+b^{2}}}\sin \left(x+\alpha \right)}

Para malaman ang halaga ng anggulong

α

{\displaystyle \alpha }

α

=

{

tan

−

1

(

b

/

a

)

,

if

a

>

0

π

+

tan

−

1

(

b

/

a

)

,

if

a

<

0

{\displaystyle \alpha ={\begin{cases}\tan ^{-1}\left(b/a\right),&{\mbox{if }}a>0\\\pi +\tan ^{-1}\left(b/a\right),&{\mbox{if }}a<0\end{cases}}}

Ang ekwasyon ay naging:

a

2

+

b

2

sin

(

x

+

α

)

=

c

{\displaystyle {\sqrt {a^{2}+b^{2}}}\sin \left(x+\alpha \right)=c}

Pansinin na ang ekwasyon ay pinasimple dahil sa paghalili ng identidad sa termino ng isa lamang punsiyon na trigonometriko. Sa kasong ito ay sa punsiyong sine (sin) na lamang.

Ngayon, hatiin (divide) ang parehong panig ng ekspresyon, ng :

a

2

+

b

2

{\displaystyle {\sqrt {a^{2}+b^{2}}}}

sin

(

x

+

α

)

=

c

a

2

+

b

2

{\displaystyle \sin {\left(x+\alpha \right)}={\frac {c}{\sqrt {a^{2}+b^{2}}}}}

Ang ekwasyon ito ay nasa anyong

sin

x

=

n

{\displaystyle \sin x=n}

x

=

α

+

2

k

π

{\displaystyle x=\alpha +2k\pi \,\!}

x

=

π

−

α

+

2

k

π

{\displaystyle x=\pi -\alpha +2k\pi \,\!}

kung saan ang :

α

=

sin

−

1

n

{\displaystyle \alpha =\sin ^{-1}n\,\!}

k

{\displaystyle k}

intedyer .

Halimbawa, lulutasin natin ito:

sin

3

x

−

3

cos

3

x

=

−

3

{\displaystyle \sin 3x-{\sqrt {3}}\cos 3x=-{\sqrt {3}}}

Sa kasong ito, meron tayong:

a

=

1

,

b

=

−

3

,

c

=

−

3

{\displaystyle a=1,b=-{\sqrt {3}},c=-{\sqrt {3}}}

a

2

+

b

2

=

1

2

+

(

−

3

)

2

=

2

{\displaystyle {\sqrt {a^{2}+b^{2}}}={\sqrt {1^{2}+\left(-{\sqrt {3}}\right)^{2}}}=2}

α

=

tan

−

1

(

−

3

)

=

−

π

3

{\displaystyle \alpha =\tan ^{-1}\left(-{\sqrt {3}}\right)=-{\frac {\pi }{3}}}

Ilapat ang nasa taas sa identidad na trigonometriko na

a

2

+

b

2

sin

(

x

+

α

)

{\displaystyle {\sqrt {a^{2}+b^{2}}}\sin \left(x+\alpha \right)}

Ang ekwasyong

sin

3

x

−

3

cos

3

x

=

−

3

{\displaystyle \sin 3x-{\sqrt {3}}\cos 3x=-{\sqrt {3}}}

a

2

+

b

2

sin

(

x

+

α

)

=

c

{\displaystyle {\sqrt {a^{2}+b^{2}}}\sin \left(x+\alpha \right)=c}

2

sin

(

3

x

−

π

3

)

=

−

3

{\displaystyle 2\sin \left(3x-{\frac {\pi }{3}}\right)=-{\sqrt {3}}}

Ngayon, hatiin (divide) ang parehong panig ng ekspresyon, ng :

2

{\displaystyle 2}

sin

(

3

x

−

π

3

)

=

−

3

2

{\displaystyle \sin \left(3x-{\frac {\pi }{3}}\right)=-{\frac {\sqrt {3}}{2}}}

Kung gagamitin natin ang pormula na

sin

x

=

n

{\displaystyle \sin x=n}

sin

3

x

−

3

cos

3

x

=

−

3

{\displaystyle \sin 3x-{\sqrt {3}}\cos 3x=-{\sqrt {3}}}

3

x

−

π

3

=

−

π

3

+

2

k

π

⇔

x

=

2

k

π

3

{\displaystyle 3x-{\frac {\pi }{3}}=-{\frac {\pi }{3}}+2k\pi \Leftrightarrow x={\frac {2k\pi }{3}}}

3

x

−

π

3

=

π

+

π

3

+

2

k

π

⇔

x

=

π

9

(

6

k

+

5

)

{\displaystyle 3x-{\frac {\pi }{3}}=\pi +{\frac {\pi }{3}}+2k\pi \Leftrightarrow x={\frac {\pi }{9}}\left(6k+5\right)}

kung saan ang

k

{\displaystyle k}

intedyer .

↑ "trigonometry" . Online Etymology Dictionary.↑ Gaboy, Luciano L. , trigonometriya, tatsihaa(n) - Gabby's Dictionary: Praktikal na Talahuluganang Ingles-Filipino ni Gabby/Gabby's Practical English-Filipino Dictionary, GabbyDictionary.com ↑ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 72, 4.3.13–15

↑ "The Elementary Identities" . Inarkibo mula sa orihinal noong 2017-07-30. Nakuha noong 2011-09-28 .{{cite web }}: CS1 maint: date auto-translated (link )↑ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 72, 4.3.9

↑ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 72, 4.3.7–8

↑ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 73, 4.3.45

↑ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 72, 4.3.16

↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Weisstein, Eric W. "Trigonometric Addition Formulas" . MathWorld ↑ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 72, 4.3.17

↑ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 72, 4.3.18

↑ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 80, 4.4.42

↑ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 80, 4.4.43

↑ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 80, 4.4.36

↑ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 72, 4.3.24–26

↑ Weisstein, Eric W. "Double-Angle Formulas" . MathWorld ↑ Weisstein, Eric W. "Multiple-Angle Formulas" . MathWorld ↑ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 72, 4.3.27–28

↑ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 72, 4.3.20–22

↑ Weisstein, Eric W. "Half-Angle Formulas" . MathWorld ↑ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 72, 4.3.31–33

↑ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 72, 4.3.34–39

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}e_{0}&=1\\[6pt]e_{1}&=\sum _{1\leq i\leq n}x_{i}&&=\sum _{1\leq i\leq n}\tan \theta _{i}\\[6pt]e_{2}&=\sum _{1\leq i<j\leq n}x_{i}x_{j}&&=\sum _{1\leq i<j\leq n}\tan \theta _{i}\tan \theta _{j}\\[6pt]e_{3}&=\sum _{1\leq i<j<k\leq n}x_{i}x_{j}x_{k}&&=\sum _{1\leq i<j<k\leq n}\tan \theta _{i}\tan \theta _{j}\tan \theta _{k}\\&{}\ \ \vdots &&{}\ \ \vdots \end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9a1d7a75d1ce780643b0b3bc40f9ad3c03ed2b44)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\sec(\theta _{1}+\cdots +\theta _{n})&={\frac {\sec \theta _{1}\cdots \sec \theta _{n}}{e_{0}-e_{2}+e_{4}-\cdots }}\\[8pt]\csc(\theta _{1}+\cdots +\theta _{n})&={\frac {\sec \theta _{1}\cdots \sec \theta _{n}}{e_{1}-e_{3}+e_{5}-\cdots }}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2c82ca2d8da55d938d78aad99295a11f79665fde)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\tan {\frac {\theta }{2}}&=\csc \theta -\cot \theta \\&=\pm \,{\sqrt {1-\cos \theta \over 1+\cos \theta }}\\[8pt]&={\frac {\sin \theta }{1+\cos \theta }}\\[8pt]&={\frac {1-\cos \theta }{\sin \theta }}\\[10pt]\tan {\frac {\eta +\theta }{2}}&={\frac {\sin \eta +\sin \theta }{\cos \eta +\cos \theta }}\\[8pt]\tan \left({\frac {\theta }{2}}+{\frac {\pi }{4}}\right)&=\sec \theta +\tan \theta \\[8pt]{\sqrt {\frac {1-\sin \theta }{1+\sin \theta }}}&={\frac {1-\tan(\theta /2)}{1+\tan(\theta /2)}}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/326123dd3bf35559b5dea3da4eff40ec130dc972)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\cot {\frac {\theta }{2}}&=\csc \theta +\cot \theta \\&=\pm \,{\sqrt {1+\cos \theta \over 1-\cos \theta }}\\[8pt]&={\frac {\sin \theta }{1-\cos \theta }}\\[8pt]&={\frac {1+\cos \theta }{\sin \theta }}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/66db927cd35c6e8d6a398351ed37ba7ce9e8c031)

![{\displaystyle |\sin x|={\frac {1}{2}}\prod _{n=0}^{\infty }{\sqrt[{2^{n+1}}]{\left|\tan \left(2^{n}x\right)\right|}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/71abcbf6e9d8704e6030ef84b53d6de4a37681ce)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {a-b}{a+b}}={\frac {\tan \left[{\tfrac {1}{2}}(A-B)\right]}{\tan \left[{\tfrac {1}{2}}(A+B)\right]}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a1da4e06eb6f25cd7f7fc1a7784a11a82ae53f9f)